Southern Tense is a continuation of Overgrown South. Overgrown South considers the tension between the South of the past, a contemporary South, and how it is often portrayed in a broader culture, “through recognizable and at times stereotypical images.”

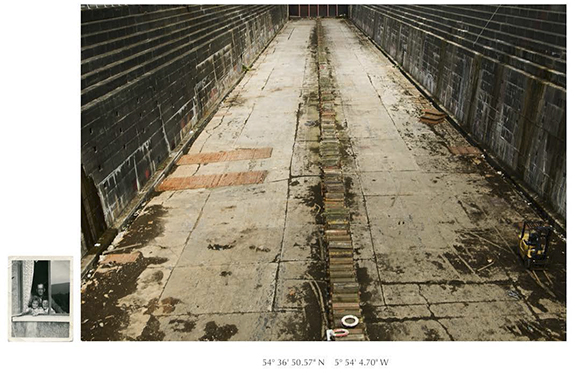

Southern Tense considers the ambiguity of a place that is defined by something as nebulous as time. Locations are not mentioned but these are visible features of the Southern United States landscape — not necessarily untouched or natural but topographical inflection, realistic and detailed through geography, autobiography and metaphor.

— Shaun H. Kelly, Oxford, Mississippi, USA