This stunning book from Ricardo Dominguez Alcaraz, a Spanish artist, is a step up in the world of print-on-demand. The images were selected and sequenced by José de Almeida, of the Camera Infinita publishing house. Peecho, the Amsterdam-based print-on-demand company, printed the book with subtle color and tonal variations.

My copy was mailed to me from Seattle, USA, and I understand that Peecho uses a distributed model of printing, with partners around the world.

Alcaraz told me that he and Almeida supplied images that they thought would print well through Peecho and were pleased with the first copy of the book they ordered. (Another Peecho user told me that he had to order a sample book and then resubmit his images after some toning adjustments.) In any case, the book is more attractive than ones I have made through Blurb, and quite a bit less expensive. I will be using Peecho in the future for my self-publishing.

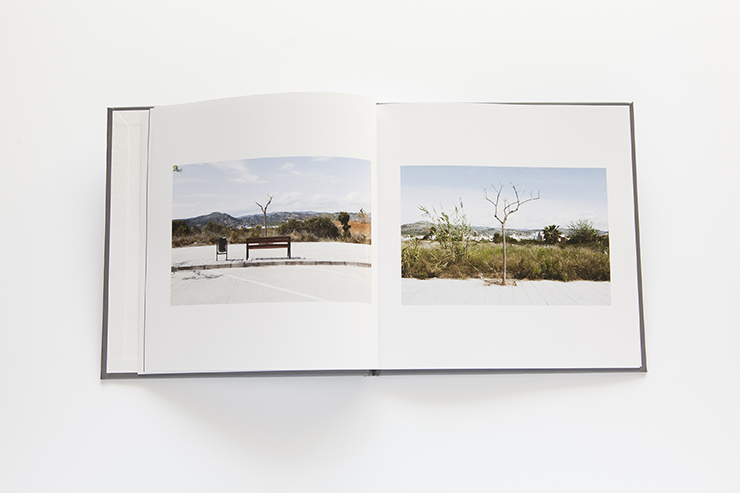

Alcaraz’s book is full of intriguing images of suburbs, “intermediate places that are absolutely necessary for the city,” according to his introduction. My only complaint about the book is that Alcaraz’s thoughtful introduction is rendered in not-quite-perfect English. This is made up for by the eloquence of his images, which can be universally appreciated. He makes a poetry of wooden pallets, stunted trees, billboards, roadsigns and other ephemera of the suburbs.

Almeida skillfully sequenced the images into a flow that links one picture to another, building a work that is more powerful than any individual image. His touch demonstrates the value of a careful and thoughtful editor. Alcaraz told me in an email that he saw his work with fresh eyes when presented with Almeida’s sequences.

No One’s Land is a treat, and reminds me once again of how powerful the printed image can be when sequenced into a carefully-made book.

— Willson Cummer, Fayetteville, New York, USA