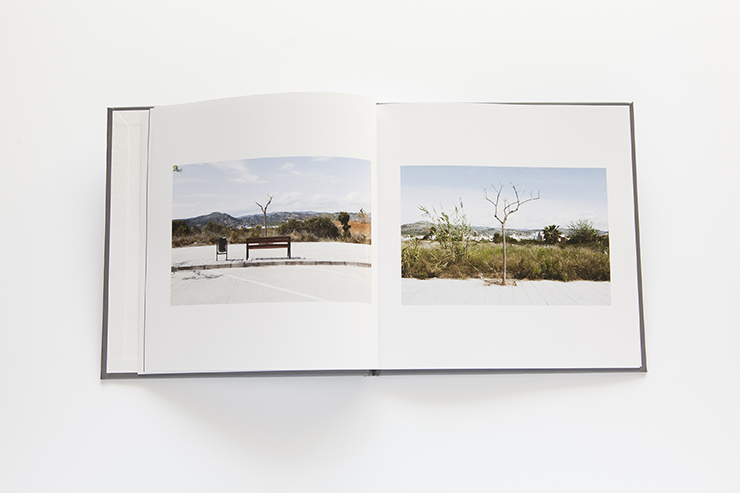

Max Sher, of Moscow, spends his time as an artist in the back streets and quiet spaces of modern-day Russia. He recently published Palimpsests, his second book.

I had some difficulty with the title, and needed the dictionary, as I’m sure most people would. Merriam-Webster defines a palimpsest as “writing material (such as a parchment or tablet) used one or more times after earlier writing has been erased.” And “something having usually diverse layers or aspects apparent beneath the surface.”

In an email exchange, Sher said he wanted to use the term to draw attention to the layers of landscapes: the pre-Soviet, the Soviet, and the contemporary. All exist delightfully jumbled together in his images.

Sher’s pictures are still, but very moving. He rarely includes people, so one’s attention goes to the buildings of various ages, designs and states of repair.

In an image below that shows a small group of people (tellingly, they are in the shadows), Sher contrasts the striking appearance of a tall tower in the distance with a foreground of an aging iron railing, concrete walls covered with graffiti, and a shabby lane that appears to be both a sidewalk and an informal parking area.

Also below is an image that at first glance appears to be of a playground: there’s a big tire filled with sand and a couple of basketball hoops. Then one notices the barbed wire at the top of the walls and it seems more like a prison recreation yard. And this is where the concept of “palimpsest” becomes so helpful: there’s a kind of nightmare in which one thing becomes confused with another beneath its surface: a prison becomes a playground and vice-versa. A sidewalk becomes confused with a parking lot.

Sher included over 100 images in the book. He created an online flip-through of the entire book.

I asked Sher why this project was so important to him (he spent seven years on it). In an email he told me:

“The urge was to create a visual language of my own with a twofold purpose: on the one hand to overcome the heritage of the Soviet Socialist Realism (when photography and other arts were supposed to depict life “how it should be”, and not “how it is”, and that’s why the landscape of the everyday was almost non-existent in, stamped out from the Soviet photography as a viable theme in itself, although it did exist in Russian photography before Socialist Realism took over (in early 1930s); on the other hand, realizing how the post-Soviet area is still mostly depicted outside – as still a very “exotic”, “other”, “weird”, etc place, I wanted to challenge that perception too by focusing on the mundane, not weirdness or exoticism, the latter being rather mental constructions than something that exists here in “real life”.

Sher’s achievement is to show the wild diversity of landscapes in modern-day Russia, and to suggest thereby a confusion in Russian life itself. The value of his book is that the confusion of spaces and lives exists in many other parts of the world.