I’m sharing five books that I came across in the past year that I found inspirational. I’ll review them in alphabetical order of the authors’s names.

Robert Adams, Tree Line

Photos of trees in eastern Oregon. Loose compositions that feel conversational in tone. Somehow in Adams’s hands an image of trees, a road and telephone wires becomes a lovely form that invites repeated viewings. Adams includes shots that were taken within minutes of each other at the same scene, thus creating what seem like still shots from a movie. Much of Adams’s work shows humankind’s destruction of nature, but this project often includes purely “natural” scenes. Adams writes that his images “recall a consolation always and everywhere the same: the promise inherent in nature’s beauty.” What follows from the recognition of that beauty is the great sadness at its loss, which Adams has eloquently explored in earlier projects.

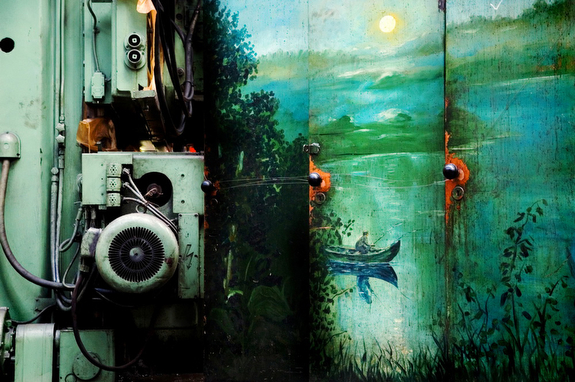

William Eggleston, The Democratic Forest

Eggleston finds beauty in the most mundane scenes. His images include trees, fields, intersections, telephone poles, signs and decaying buildings, but his true subject is color and form. He appears to have used a 35mm camera (he’s holding one in the author photo), in an interesting change from the work of Stephen Shore, Joel Sternfeld and others who have used 8×10 cameras to photograph similar subjects. One of my favorite images is untitled (p. 59) and shows a parking area behind a few buildings. On the left is a dark green structure. To the center is a brick and cinderblock building and on the right is a blue car, dazzling in the direct sunlight. Starting at the bottom right and wending their way toward the upper left are sets of lime-green footsteps stenciled onto the blacktop. So mysterious and beautiful. Another memorable image is a photo of mud, a chain, and two mud-stained boots and jean legs — photographed at an oil rig. The yellow-orange of the mud spreads over the chain and clothing — as if the earth were swallowing up the person foolish enough to try to extract nature’s riches. The book includes an introduction by Eudora Welty and an afterword by Eggleston.

Andy Grundberg, Crisis of the Real

Intellectual criticism that makes sense and is fairly easy to follow. Grundberg presents an insightful discussion of postmodernism, comparing the meaning of that movement in various artistic genres. A chilling conclusion: “There is no place in the postmodern world for a belief in the authenticity of experience, in the sanctity of the individual artist’s vision, in genius, or originality.” (p. 18) That’s why I continue to struggle with postmodernism. Grundberg includes illuminating essays about the work of Walker Evans, Robert Adams, Joel Sternfeld, Richard Prince and Sophie Calle, among many others.

Ken Schles, Oculus

Part philosophical text, part photobook, Oculus is a tantalizing publication. Schles includes references to many sources, touching on Plato, Vladimir Nabokov, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and others. The book includes gorgeous images from three very different projects: portraiture of children sleeping, nighttime beach photography and a varied series of images gathered under the title “Mnemosyne,” for the Greek goddess of memory and the inventor of reason and language. Schles includes lengthy notes, which give the reader multiple access points to the book. His mysterious chapter titles, like “Seeing Is Not Knowing,” challenge the viewer to connect Schles’s philosophical musings to the images.

Dale Schreiner, Thereafter

Meditations after the shooting death of his father. Stunning tones, interesting subjects. Very well sequenced, with logical connections between all the shots. Schreiner opens the project with an image of a road and a four-sided sign that we see from behind. He photographed from a tangled scrub land off the road, with a short fence between him and road. The path toward the future, Schreiner seems to be saying, is not easily found or followed. Even road signs, placed there for guidance, may be worthless. Trees are a recurring element in Schreiner’s images, and they are at times bent in half, wrapped with small ropes or set behind fences. In one image a tree stands behind a ribbon that warns “danger.” The consolation that Robert Adams wrote about is simply not present in Schreiner’s work, though the subject matter is similar. Thereafter was published by Vela Noche Press in an edition of 20 books.

— Willson Cummer