I lived in Southern California and the Nevada desert for a decade. This series started during my Christmas trip to visit my daughter. I developed appendicitis and was hospitalized for several days. I couldn’t really walk much afterwards and started shooting near by. In Nevada we would often visit these types of sites, always aware of the weather and flash flood conditions. I’d say half of my work is in the desert. Sometimes before going out on a photo trip we watch Gunsmoke or Bonanza — just to get the feel again! I grew up on westerns and felt right at home when I arrived.

My love of dry desert creeks and underground streams started as soon as I moved to the Southwest. Standing in these dry creek beds you can “hear” the water flowing, but it is really the sound of the wind flowing through the rock beds. In the flatter areas you find the stream bed by waiting and looking for a visual clue that signals the path long unused. As a child growing up in the woods of the Northeast I often followed animal trails through the wood. Broken branches, hard pressed dirt, lesser density of bush gave away the path.

Santiago Creek, where I now find myself, stretches across Orange County, California, for about 34 miles. The stream appears and disappears, sometimes hard to navigate. It starts its life between Santiago Peak, the highest peak in the county, and Modjeska Peak, which together form the prominent Saddleback of the Santa Ana Mountains, often visible from the creek bed itself. Its headwater rises towards the Santa Anna river, first running south-southwest toward Portola Hills before turning northwest. Downstream it receives Baker and Silverado Creeks and then after Santiago Canyon Road the gorge widens to a broad alluvial plain. The banks are now visible in the distance. The flow of water is limited to this upper stretch; below water flows underground except during the winter and early spring. Still, along its path water can percolate and sit on the surface. Following this path brings about a sense of knowing where I am.

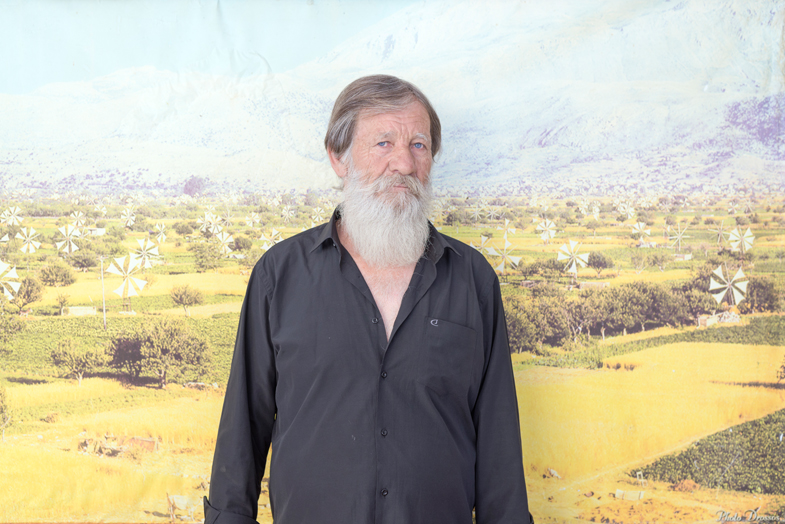

— Jim Roche, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada