www.PeterCroteauPhotography.com

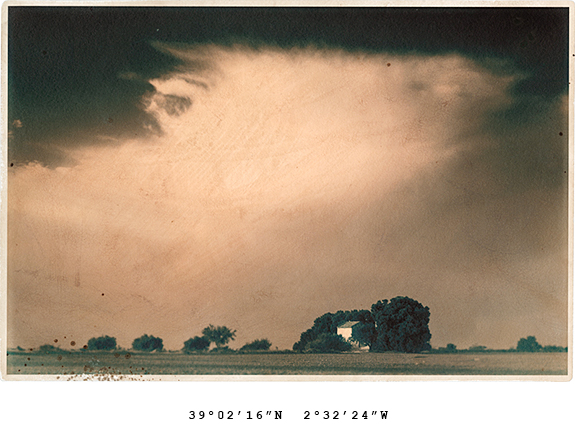

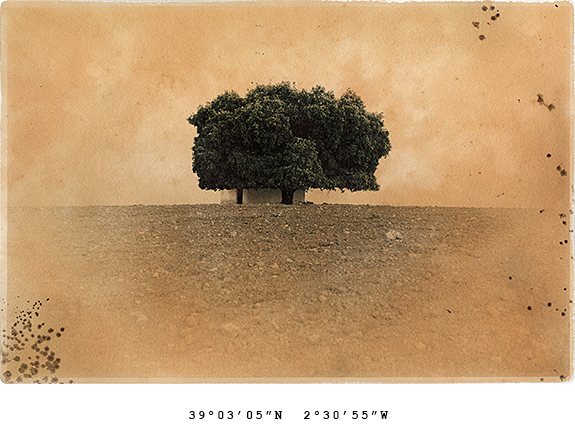

Spaces of dross are the in-between waste spaces in the landscape. Left as a result of sprawl, these spaces are in a constant state of flux between use and disuse. I explore these mundane spaces using the camera as an apparatus that can reframe and order the world. Through my use of the large format camera I create images of dross that also function as markers of the sublime. In focusing on spaces of dross, but using my camera more like a canvas, I set up a dualistic relationship between earth and sky in order reference painterly representations of the sublime. This relationship speaks to a high/low binary that exists in the American landscape between spaces of preservation and spaces of waste, humans’ free will to shape land and its use, as well as the ideologies that define the way we understand natural forms.

Peter Croteau, Providence, Rhode Island, USA