www.John-Sanderson.com

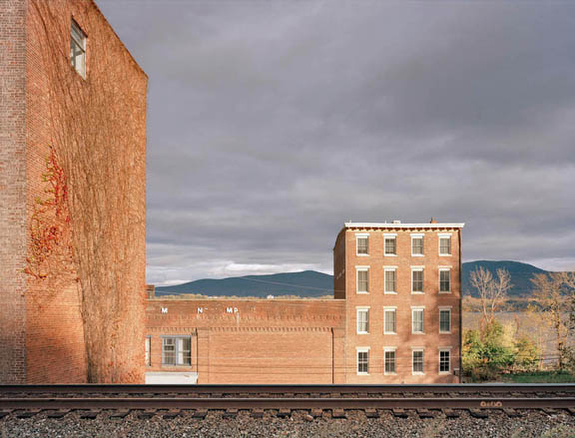

“He knew at once he found the proper place. He saw the lordly oaks before the house, the flower beds, the garden and the arbor, and farther off, the glint of rails…” — Thomas Wolfe

A common theme in my work is the contextual depiction of structures implying movement.

Space changes around rail lines that remain generations after their construction, places retaining a quality of transience and continual movement. The tracks flow into the distance or cut across a picture, leaving us in wonder; and yet their confident line anchors one to its path. Once bustling depots sit forlorn, objects of aesthetic pride became forgotten white elephants. Elsewhere, tracks flow through immutable mountain passes.

These images are a metaphorical depiction of the railroad spirit that has imbibed the American psyche since its inception. The railroad has often been seen as an avenue of hope, loss, beauty, redemption, and so on. As a document of the contemporary railroad and a realization of Form between a rail line and the environment, these images are couched in a use of light, color, weather and shape that attempt to give the pictures a flickering, temporal quality — the allegorical representation of movement.

— John Sanderson, New York City