www.AdamAndMartenePhotography.com

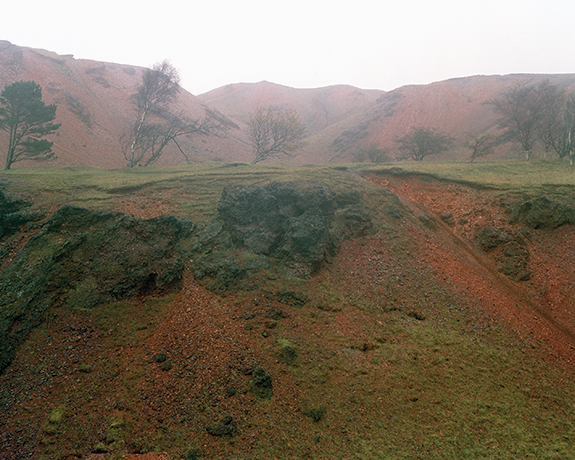

The series Urban Wilderness depicts areas of land within various European cities which have been left unused for a period of time, where subsequently nature has been left to its own devices. These spaces lie in an intermediate state as land is bought and sold, decisions are made and plans are drawn. In some cases these spaces have been left for so long they appear to have been forgotten.

Spaces such as these are mostly closed off from the general public and often in order to enter it is necessary to overcome physical obstacles such as walls or fences. These obstacles establish the fact that these spaces are not there for the public to enjoy. They are privately owned pieces of land bought for the purpose of private business development.

These temporary havens of nature which are surrounded by the built environment contrast starkly with the controlled form of nature that we experience within city parks and gardens. They serve as a reminder that nature is always waiting to reclaim space whenever the opportunity arises.

— Martene Rourke & Adam Heiss, Manchester, United Kingdom