www.MBachPhoto.wix.com/Michael-Bach

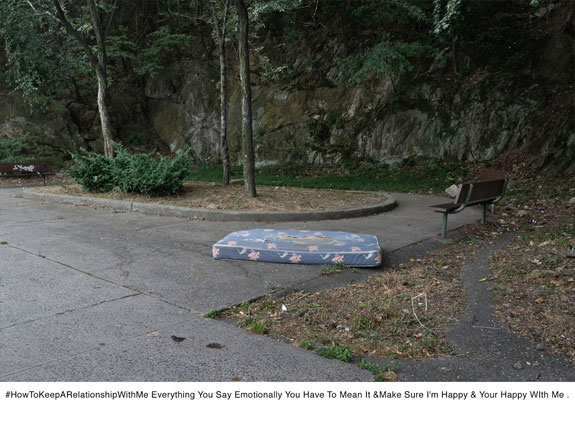

There is a palpable sense of sadness and despair felt when walking in the woods and fields of Mt. Ida, as if a dark veil enshrouded the landscape. While stumbling across remnants of failed lives and desperate attempts of domesticity, one cannot help to think of those forced to endure such hardship. In 2010, the city of Troy, New York permanently banished the homeless from the land. It was then that I chose to carry out the project Displaced, to be a memorial to the landscape and a testament to the people who called this place home.

In photographing, I was less interested in literally documenting what I came upon and more in the narrative contained in the personal ephemera, belongings, and structures for living. I wanted to avoid personal bias or the overt social and political implications of the subject matter, allowing the spirits of this neglected landscape to shine through. The photographs are intentionally left open-ended. In the end, the viewers will have their own personal experiences when viewing the work.

During the time I have been working, construction projects have threatened and overtaken portions of the land. I dutifully photographed what was to be eliminated. Presently, the construction of another building has eradicated the landscape once more. Eighty percent of what I have photographed no longer exists. This includes the landscape itself, as well as what was left behind by the homeless. I fear that much of the land of Mt. Ida will, slowly but surely, succumb to this conflicting relationship between man and nature.

— Michael Bach, Troy, New York, USA