Fallen Giants seems to be the most intimate of your projects. How did it start ?? When will it be completed ?? How will you know ??

Fallen Giants is the most intimate series that others can see. I have made very personal work in the past, so personal indeed that I don’t choose to show it to anyone. Sometimes work can be therapeutic, or the only outlet when going through a difficult time. During my mother’s cancer, I made a lot of written and visual pieces to help me deal with that nightmare.

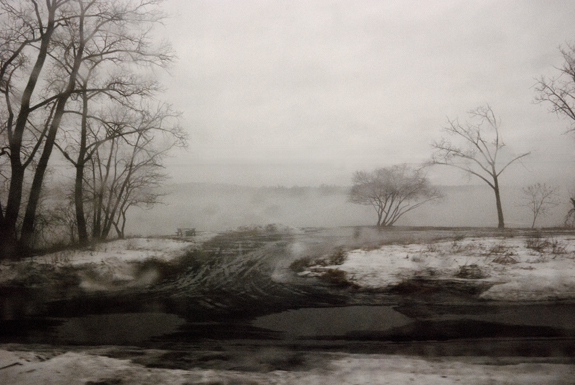

Fallen Giants began in my head with some words my mother said before she died. She had gone to Florida to rest, after the grueling chemo, and when she came back home, she noted, very sadly, that things seemed to be falling apart on the farm, and that it looked rather ramshackle. “I always thought it was perfect here, but things look so shabby.” She was seeing her mortality in her intimate surroundings, I thought.

It has been twenty years since then and the old outbuildings are as fragile as my 96-year-old Dad. I want to image the relationship between his physicality and the structures bending with age about him. It has been noted that people become like their pets; I think people also become like the spaces they inhabit or vice versa.

I will photograph there throughout the seasons and the time I have left with him. These days I make plans to go there to make more images but something pulls me back. I allow the internal feelings on this one to lead me to continue, to tell me when to go, and when to stop.

What photographers inspire you ??

The photographers I love the most have a quality in common with me, although their images are not like mine at all. There is a subtle intimacy between the personal and the subject; I feel I am looking through their eyes. I can feel the photographer ‘s intelligence, behind the camera’s back. It is that moment when the camera disappears and one is face to face, engaged, with the subject.

I melt before the work of Robert Frank, Robert Doisneau, Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Martin Chambi, Hiroshi Watanabe, Diane Arbus, Eugene Richards, and, most recently, Vivian Maier. What an eclectic bunch!

I feel the same way every time I stand before a Van Gogh.

Your projects usually involve portraiture. For Fallen Giants you mixed in landscape and still life images. How did you decide on that mix ??

I didn’t make the distinction between those genres as I made the images. They are parts of a whole, as one would photograph the whole body or a close up of one part, an eye, a hand.

Writing is very important to your projects. How did you develop your writing skills over the years ?? Does it help your shooting to be able to write so clearly about what you are doing ??

To my mind, photographs are like jumbled sentences, with parts that can be diagrammed to make sense. One mentally assembles the meaning based on one’s personal experience and culture.

I don’t think about what I mean while I am doing it. I click the shutter, experiencing a moment of engagement. It is in the editing that I can start to write about what I have made and what it means to me. Words help the viewer, and me, assemble the meaning.

I really have done nothing to develop my writing, other than doing it. I am drawn to words in images, and the complex play between thought, text shapes, and meaning.

You teach professionally. How do you like that ?? How does it affect your photography ??

Without teaching, I don’t believe I would have remained as passionate about photography as I am. My young students inspire me with their passion and excitement. I found exactly what I am meant to do in this world. It is a joy.

You usually shoot film. How does that affect your work ??

Sometimes I shoot film. Sometimes I work with found images and work digitally. I tend to work digitally in the months when Chicago weather keeps me inside. I have to work on something every day. So I have about five projects going on simultaneously in order to pick and choose.

I really love black-and-white film, as much as I love objects. I have six houses in Capricorn (no eye-rolling, please) so that explains my attachment to physical things. I am on the verge of becoming a hoarder.

My favorite part is developing the film itself. Agitating the canisters, being accurate in the science of it, thinking about how the film is changing inside, and waiting to see the magic. I love film cameras as well, beautiful and functional objects. Medium format is what I prefer; the square is so perfect, so orderly.

— Interview conducted and edited by Willson Cummer