There’s a time at the outset of some days, when for a few moments I exist in that narrow zone between dream and waking reality. During that gradual rise to consciousness, the dream reality becomes dim and recedes into the distance, and I often struggle to imprint the disappearing image of it on my memory.

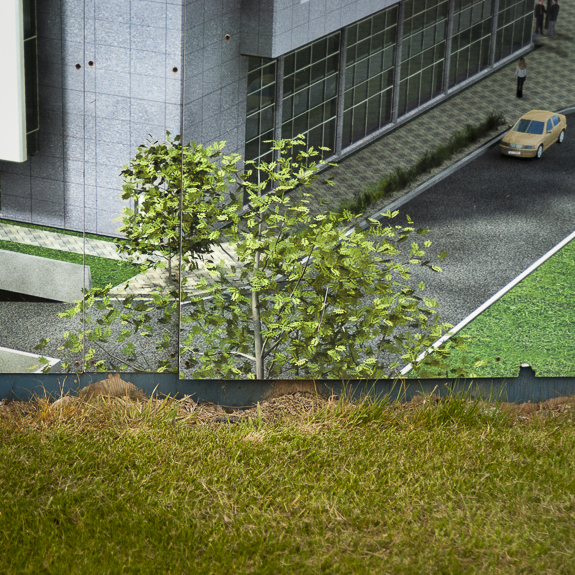

I’m very interested in these half-remembered scenes: landscapes that exist in waking reality and later in dreams, filtered by my unconscious in service of some narrative that my brain has created to maintain itself; but these images can’t be captured by any conventional photographic media. Once appropriated for dreams, they exist only as memories or suggestions of the physical world. They fade quickly.

There are occasions though, while out looking for pictures, when a scene will present itself to me with elements that are evocative of a future dreamscape. In Dreams is an open-ended collection of images where I’ve been guided by that suggestion.

— Dave Reichert, Pecos, New Mexico, USA