Twice a day for ten years, formerly with my companion Barney the dog, I walked a circular route along this small stretch of river close to my home in northern England, often in the pouring rain, frequently in the freezing pitch dark.

I calculate that, taking occasional absences into account, we walked this route approximately nine thousand times.

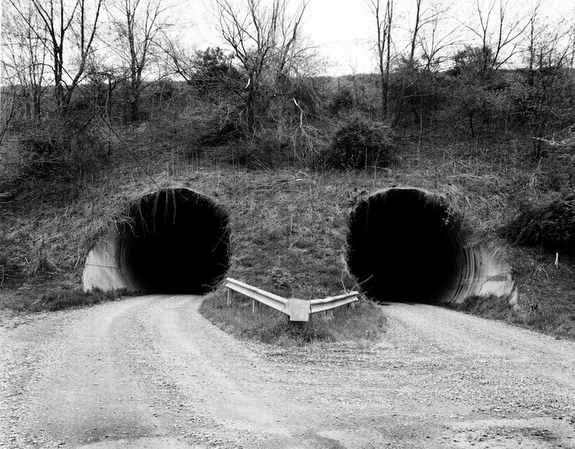

The river marks a boundary between the city and the arable (farm) lands and is not only a favourite spot for the dumping and burning of stolen cars or for junkies to hang out; but is also used by dog walkers (myself included) and as an adventure playground for the local kids. For many it is invisible, a non-place passed by on the way to greater treasures in the city or the countryside real and as such becomes its own place free of any expectations of ever being more than it is.

— John Darwell, Carlisle, United Kingdom