www.JPGauvrit.net

Most of my projects are related to China, watching its economic, social and urban development, trying to understand this country and its people with my western eyes, tracking the promises of the future in the perpetual move of the country and its cities.

Pudong is the modern economic and residential district of Shanghai, located at the Eastern side of the Huangpu River. A few decades ago, it used to be a vast farming land, surrounded by water, whose recent modern development was decided and initiated by Deng Xiaoping at the end of the Cultural Revolution period, to become a flagship of a new prosperity era.

Beside the modern and spectacular landmarks of Luijiazi, the Financial District, like the Oriental Pearl Tower, the Jinmao Tower, or the World Financial Center, offices, modern and high-rise buildings have gradually replaced the old housings, farms and industrial estates, dismantled or pushed away to the periphery of the city.

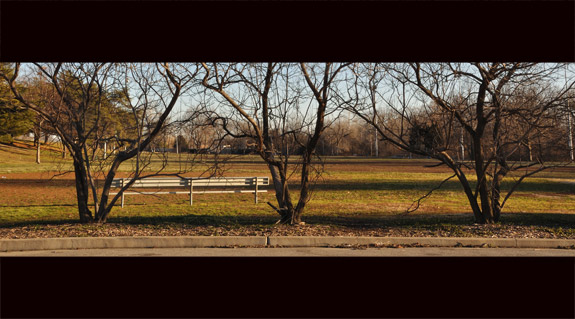

The concept of this documentary project is to follow-up a few selected avenues, which are offering a variety of landscapes, to illustrate the modern conception of the city promoted by the Chinese authorities, and watch places still under evolution and full of potentialities.

I started with Pudong Nan Lu and Pudong Da Dao avenues, which are progressing in parallel to the Huangpu River, and are running across a variety of places and patterns. I am currently working on others avenues at the south and at the east of the District. Pudong Avenues is mirroring another project I am currently developing in Shanghai, in black and white, in the District of Minhang, and I am also working in several second-tier cities of China.

To describe my photography, I would simply say “Documentary Photography.” I have a deep interest in places, spaces, and territories, in one word, in landscapes, urban landscapes. I believe that showing where people live, work, and interact can teach us as much about the inhabitants as showing them. Improbable and ugly spaces, buildings, highways, bridges, factories, train stations and railroads, how can we explain that these places seem to run their own life, growth, decay or agony, in an apparent total independence from their designers or users?

I feel comfortable walking along these places, as I am also interested in visual emptiness, and in visual banality. Sometimes I am trying to capture some essence from nothing… Maybe am I simply documenting absurdity?

— Jean-Philippe Gauvrit, Shanghai, China