Postcards from Europe 03/13, by Eva Leitolf

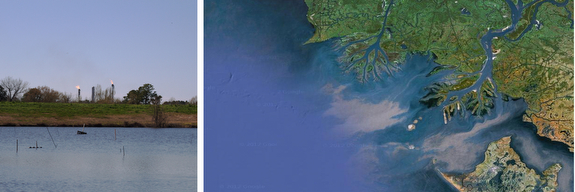

Eva Leitolf’s book Postcards from Europe 03/13 appears at first to be simply that: a collection of 20 large cards gathered together and presented as a book. The cards have 10.5 x 13″ images on the front and text on the back. But instead of cheery notes, Leitolf supplies grim statistics about the hazards of illegal immigration into Europe. She recounts deaths, riots and other affronts to the migrants.

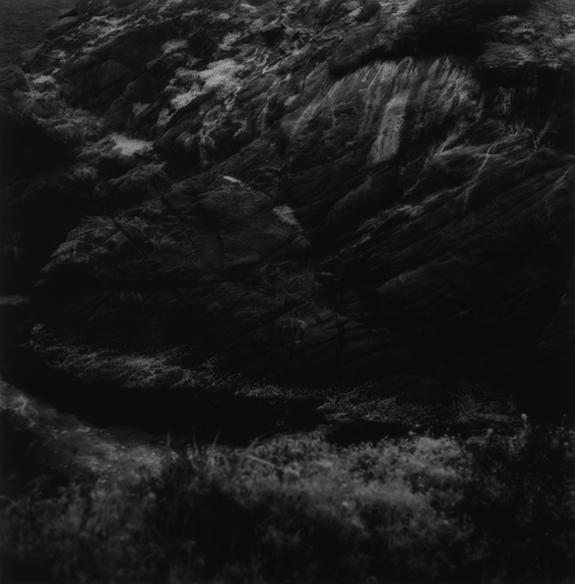

Leitolf’s images are often banal landscapes, which become filled with meaning as we move through the book. Sometimes there are clues in the images: a security fence, a pile of wooden ladders, chairs knocked over. Other times we see simply a desolate beach. Only on turning over the card do we discover that 24 bodies of would-be immigrants washed up on that beach.

The book is a collection of puzzles. Once we know that, our enjoyment of the images increases. Why are dozens of oranges on the ground under a tree in one image? What is the meaning of a humble wooden platform about 15 feet off the ground at the edge of a field? We know that we’ll have the answer once we flip the card.

Because the images in Leitolf’s book are not bound, they draw comparison to prints. This is unfortunate. The plates are printed using four-color offset presses, and are well made. But they do not approach the quality of inkjet prints or traditional color prints. (Of course one could not buy a collection of 20 prints for the price of a book — but the presentation invites comparisons between the two.)

Leitolf, a German photographer, made images in Italy, Spain, Greece and Hungary for this book. Postcards from Europe 03/13 is available from Kehrer Verlag.