One of the issues I struggle with in my life is being open. I think it stems from a fear of being judged, that in knowing the real me, I will be found lacking in some capacity and abandoned. It’s something I’ve tried to work through, a lack of faith in anything that would endure.

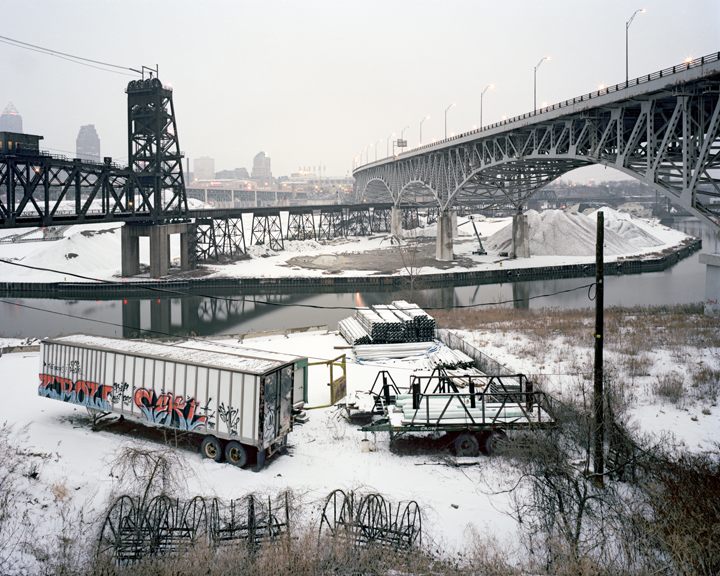

It is one of the reasons I wanted to become an architect. I thought that in imagining these built forms, I was creating something that would remain, something I could construct that would stand long after I was gone. It is also the reason why I’m so drawn to photographing the natural world, especially near urban areas.

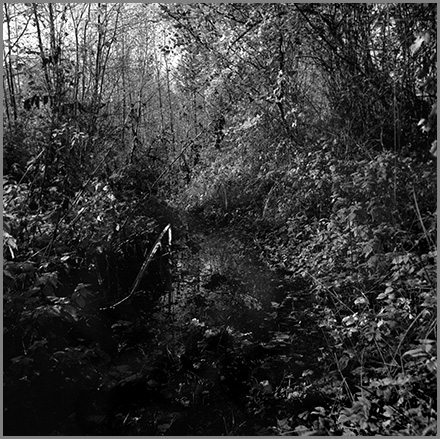

Repeatedly, the subjects that I find engaging are the ones that survive in an environment meant to exterminate as a way to answer the questions I continually grapple with: What is permanent? Will anything last?

I became obsessed with this lone tree’s form and photographed it more intensely than any subject I have ever focused on. It was alone, with its scars unclothed, threatened by vines, but still standing. I was moved by its quiet beauty and strength, within it a humble model of perseverance and survival.

— Lauren Henkin