All The Time In The World

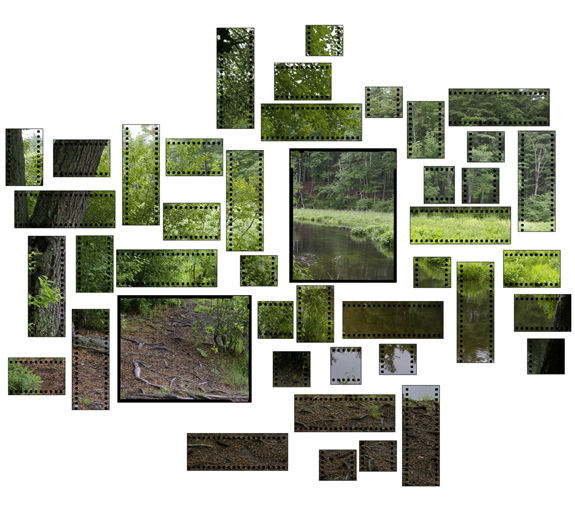

As our childhood memories slip we navigate into this new world of adulthood. We transition into this new unfamiliar phase, a completely different landscape of thought. This metaphorical landscape of youth expression transforms our lives, but we can never pin down their meanings until they already passed. We create myths of our own past to comprehend these fleeting moments that never came back us. As time goes on we return to these places of our youth only to recognize that it is not the same, just a forgotten memory of what used to be, what used to be ourselves.

These fleeting moments of life have always troubled me. They are incredibly powerful to us at the time of living it, just to be unrelentingly forgotten later. All The Time In The World came out of my need to capturing these moments of youth as a way to live within them forever. These photos depict some of my closest memories from finding first love, road tripping around California to enjoying the slow days cliff jumping with friends. These universal interactions between us no matter how forgettable make us into who we are.

— William Mark Sommer, Sacramento, California