Dungeness: The Liminal Landscape

The artist, writer and film director Derek Jarman spent much of his later life on the shingle of Dungeness at his home, Prospect Cottage. Jarman had purchased Prospect Cottage impulsively with an inheritance received from his father and used it as a second home and as a source of escape from his central London studio.

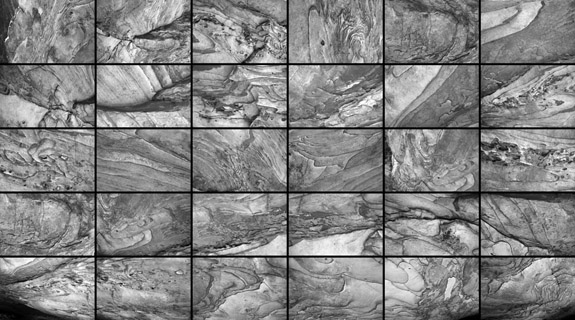

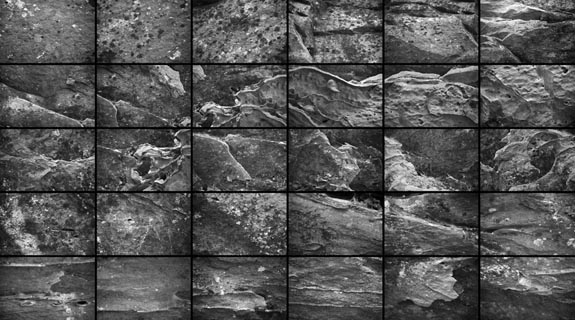

With declining health, Jarman engaged with the landscape of Dungeness and returned to his first loves of gardening and nature. Jarman described in his diary his experiences of nature and the landscape surrounding his home. Published as Modern Nature, Jarman’s diary is a poetic record of his life between 1989 and 1990, and recounts the wilderness of Dungeness and his time spent at Prospect Cottage in reflective detail.

My own time spent in Dungeness in the summer of 2020 was inspired by the literary descriptions of Jarman and a desire to engage and explore what he had found so mesmerising. My aim was to photograph the spaces he so vividly described and to create my own visual response to the landscape, as he had when writing his diary. I recorded my own written responses to the landscape in my diary as I too immersed myself in this wild place.

— Michael Crocker, Bristol, United Kingdom