25,000,000 m3 Is a study of man altered landscape created as a consequence of violence and the ideas in the physical remnants of the city.

Teufelsberg (Devil’s Mountain), located in South West Berlin and surrounded by forest, is one of the highest points of the capital. This hill is used by the city’s residents for various leisure activities such as hiking, skiing, and cycling. However its natural surroundings belie its darker origins. A partly constructed military college designed by Albert Speer originally occupied the site. In the aftermath of the Second World War the rebuilding of devastated German cities took place.

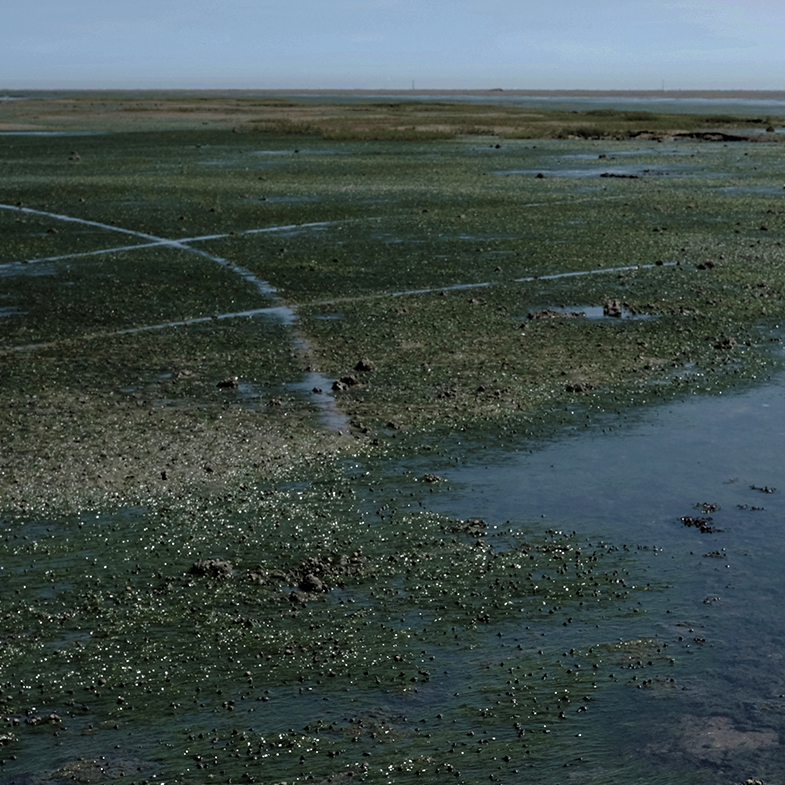

One solution to deal with building rubble left was to use the material to form a Trümmerberg or rubble mountain. Huge volumes of debris were turned into such earthworks the largest in Berlin being Teufelsberg, which also covered the ruins of the aforementioned military college. Later with the division of the city the summit of the hill was the location of an NSA listening station, now abandoned.

25,000,000 3m studies not only the surface of Teufelsberg and its landscape, but also the layers of the destroyed city it is created from. Combining images of the hill’s topography and surrounding landscape whilst revealing what is buried under the surface, I am attempting to give physical presence again to the city’s past structure and the issues that arise from this.

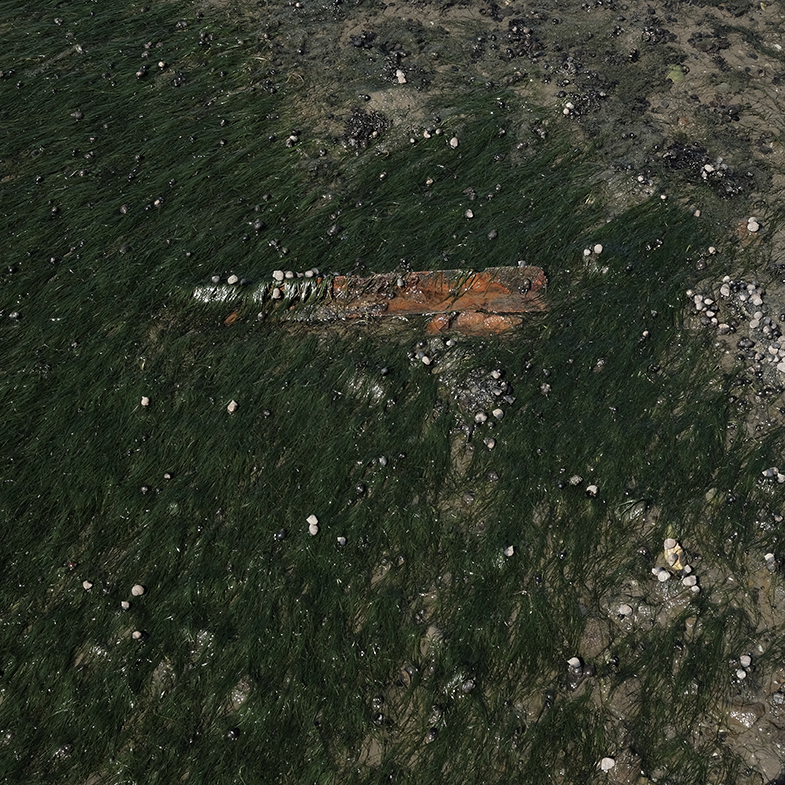

The second part of this approach is via a process of recasting the shattered building fragments found on the hill using plaster. By duplicating them but removing colour and fine texture leaving only surface details, relief of layers of residue and marks. The emphasis less about the objects as individuals, but more about the wider investigation into the absence of a city’s past buildings.

This is an attempt to explore an idea of revealing what is hidden, buried in the landscape. Glimpses and fragments of what was once the city’s structures remain, leaving it impossible to experience the buildings and landscape as a whole.

— Ben Bird, London